The cemetery is filled with endless stories. Stories about individuals that we will never meet, stories that have been passed down through the ages, ones that have been lost to time, and ones that we are able to tease out of the archives and records to tell again. Today’s story is one of those that has been pieced back together to be told again. This is the far-too-short story of Robert Cooper.

As far as the records show, Robert Cooper was born in England in 1854 to Mary Ann Cooper. At the moment, we have been unable to figure out anything about his father, as he died prior to the 1871 Ontario Census. Mary Ann arrived in London sometime between 1861 and 1871 (due to her not appearing on the London 1861 census), and we can narrow that date further to between 1861 and 1871. She first appears on the 1871 census as living in London as a widow.

It is possible she moved to Ontario to take a job as a servant after her son was born and her husband had died, leaving her with no other option than to take work overseas to support her family. Neither her nor Robert are listed on any Ontario census records prior to 1871, suggesting the arrived in the 10 years between between then and the previous census.

The W looks a bit like an ‘M’ as well, but other records of clearly married people had a different looking M, so just trust me on this one. A clear indicator that a woman wasn’t married either, along with the W in the census records, was that she wasn’t listed below her husband’s name. Mary Ann was listed alone, suggesting she may have been living with the family she worked for. Her son Robert, who was 17 in 1871 (she would have had him at age 28), is listed on a separate page of the census.

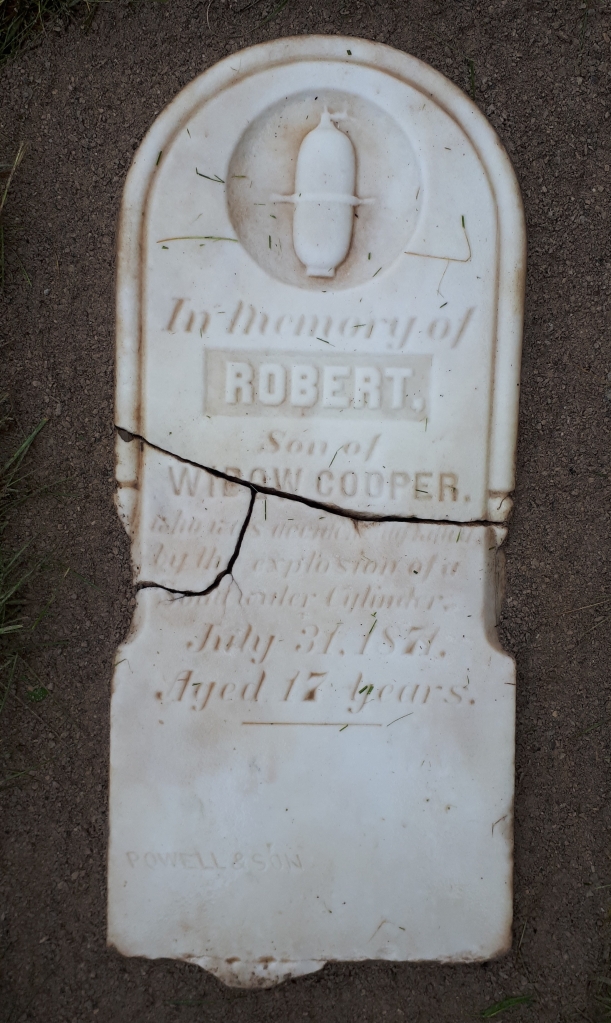

Earlier this week, Brienna was probing in a large open section of Section K and uncovered the most curious headstone that we had ever seen. As we pulled back the sod we were met with a gravestone image that was both confusing and exciting! We rushed to uncover the rest of the stone and clean it, hoping that it would reveal something about the image.

The gravestone turned out to belong to one Robert Cooper, and it read as follows:

In Memory of

ROBERT

Son of

WIDOW COOPER

who was accidentally killed

by the explosion of a

Soda water Cylinder

July 31, 1871.

Aged 17 years

____

POWELL & SON

The image on the top of the gravestone was a soda water cylinder, which would have held carbon dioxide or ‘carbonic acid’ which was forced into water to make it fizzy. This process was discovered by Joseph Priestley in the late 18th century, naming him the ‘father of the soft drink’, and became very popular! However, highly pressurized tanks are subject to explosion if the conditions aren’t right, or the tank is damaged in some way.

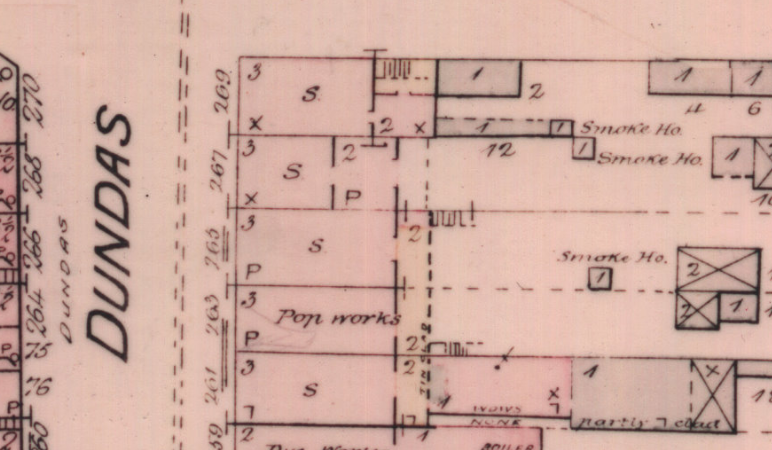

Robert was listed in the year of his death as having worked as a servant, but it does not say where or to whom he was in service. Records from the Ivey Family London Room at the London Public Library state that at Bilton’s Soda Water & Pop Works on Dundas Street, London, a ‘soda fountain’ exploded, killing Robert Cooper instantly. A newspaper article from the London Free Press, August 1st, 1871, states that he was an employee of the soda works.

Bilton’s was one of many soda works in London in the 1800s, and was near the intersection of Dundas and Wellington Streets. We haven’t been able to find out much more about the company, but are definitely looking to fill in the gaps. It may have looked similar to the water works of J. Tune & Son, which was established in 1882 on York Street. As you can see in the background of this image, there are many large tanks which would have been used to carbonate the water in the bottles. Robert was working near a similar tank, as part of his job was to ‘fill and wash the vessels’ during the soda water making process (London Free Press 1871).

“It was a jar-shaped utensil, and stood upon its bottom. While it was in this position Cooper and another young man named Welch approached it and were about to lift it by the handles. Cooper has no sooner bent over it than the fountain exploded with a terrible force, rising like a rocket and striking against the ceiling with a ford which broke through the ….. and shook the whole building. In its upward flight, horrible to relate, it struck young Cooper in the chest and under the chin, and bore him bodily up with it. His head struck against the ceiling about three feet distant; and also broke the plaster. He fell lifeless. His companion Welch was forced by the outflying gas across the floor amongst a lot of the bottom, and narrowly escaped the same fate. Dr. Fluck was at once sent for, and appeared five minutes after the accident but too late to be of service. The body was carefully removed to Mr. Bilton’s dining room, overhead, and coroner Moore notified. In the afternoon at four o’clock, an inquest was held.”

-London Free Press, Aug 1, 1871.

The tank they were filling belonged to a J.E. Baker on Richmond Street, which indicates that stores could bring their tanks/fountains over to the Soda Works to have them refilled, and that the tank in question had been repaired before for leaks. In short, it could easily have been faulty. The deposition of witnesses and owners concluded that Robert’s death was an accident due to faulty repairs of the tank, and that when tanks are leaky after that point they are to be condemned in order to prevent further tragedy (London Free Press 1871).

Our burial and death records here at Woodland list Robert’s burial as having taken place at St. Paul’s on August 1st, 1871, and that his body was transported there from the ‘City Hospital’. This indicates that he was brought to the hospital after the accident. Later, his burial and gravestone were brought to Woodland Cemetery post-1879.

It is curious that the gravestone shows a carving of the cylinder that killed him! It is not a common motif, to show on a gravestone what ultimately ended one’s life…unless that something was a boat. Additionally, his mother’s name is only listed as ‘Widow Cooper’ on the stone, an interesting choice to make as his only family.

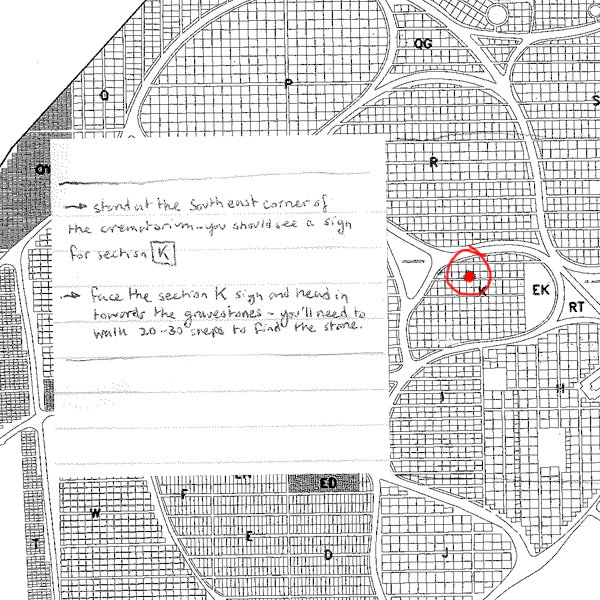

Robert’s death was a tragic accident, but through the resulting inquest into what happened, safety precautions were brought into place to protect future soda men in their places of work. We packed the space with limestone screening to allow drainage without letting the gravestone sink as quickly, and made a buffer of screening around the edges to keep the grass back as long as possible Robert’s stone can be visited in Section K. We remember Robert through his curious gravestone, which gave us a glimpse into his life in 1870s London.

Thank you for following our progress so far this summer! Keep an eye out for more information on our walking tour, which will be held on July 6th, 2019.

Curious about the newspaper article?

If you are interested in the rest of this article, check out the London Reading Room or download the sections below:

Want to see the stone for yourself?

Here’s a helpful map to aid you in your search. Let us know in the comments if you have any trouble finding the stone!